Carnegie Mellon’s bioprinted liver patches function for weeks, buying crucial time for organ regeneration. Liver failure kills while patients wait for donors, but Carnegie Mellon’s bioprinted patches could bridge that deadly gap. Over 100,000 Americans sit on transplant waitlists while millions more remain ineligible—a crisis that claims lives daily. Now researchers have cracked the code on printing functional human liver tissue that works for 2-4 weeks, potentially transforming emergency medicine.

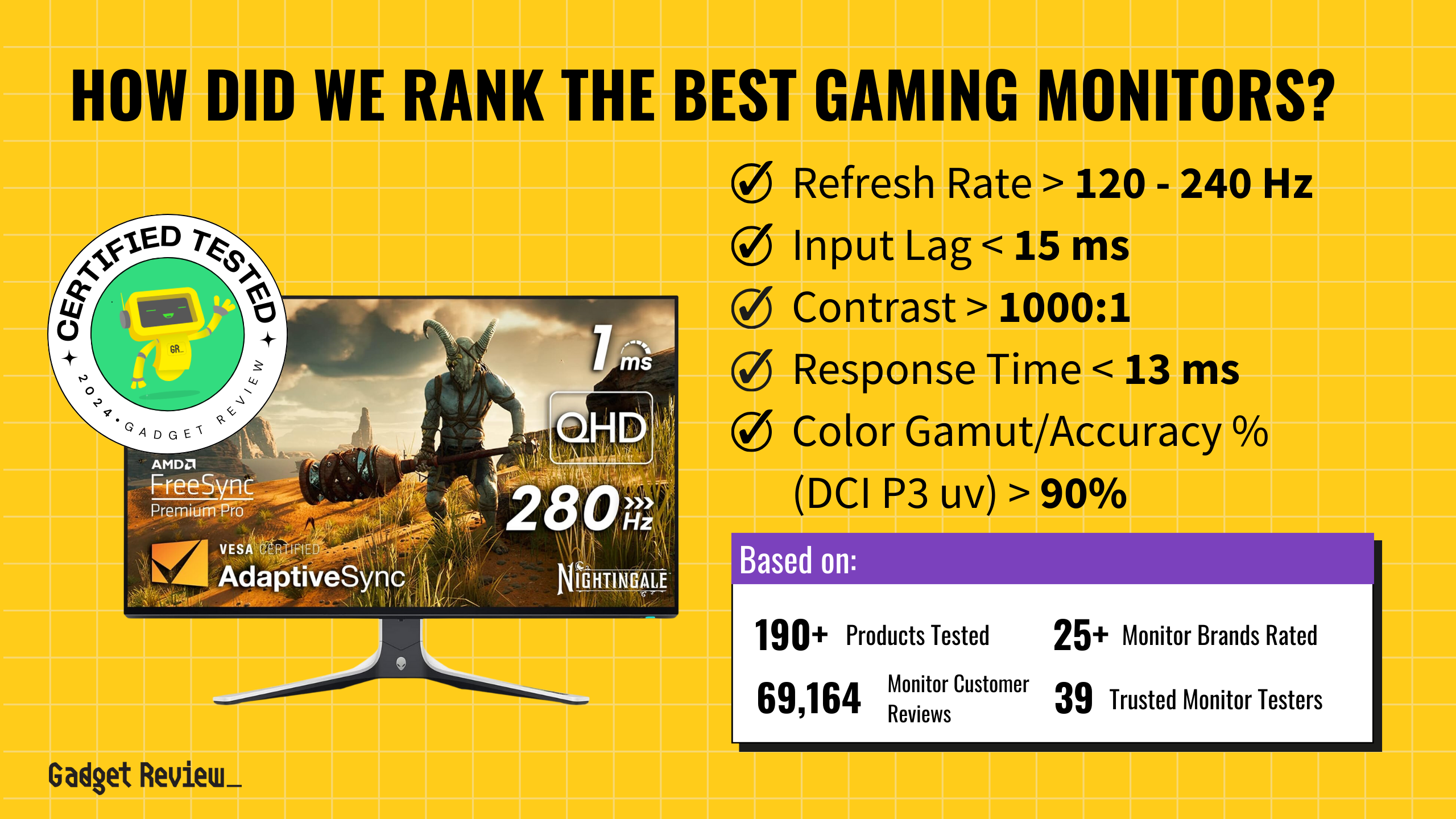

The breakthrough centers on Carnegie Mellon’s LIVE project, which just secured $28.5 million from ARPA-H to develop these life-saving patches. Unlike the sci-fi fantasy of printing entire organs, this approach focuses on temporary support—think of it as biological jumper cables for failing livers.

The Tech Behind the Medical Magic

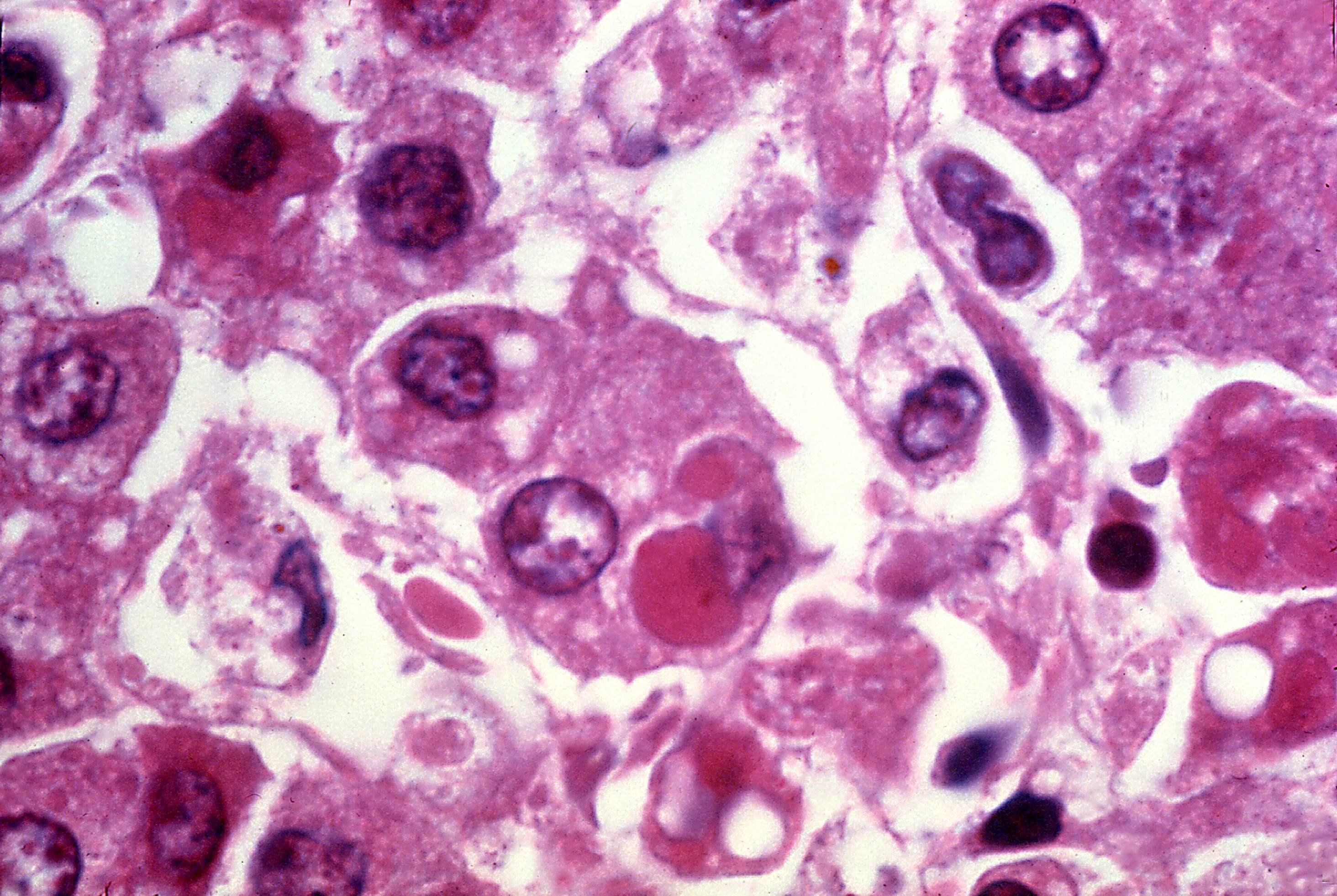

FRESH platform prints soft tissue using engineered human cells that dodge immune rejection.

Carnegie Mellon’s FRESH platform solves bioprinting’s biggest challenge: creating soft, squishy tissue that doesn’t collapse like a failed soufflé. The system prints using collagen and specially engineered hypoimmune human cells—essentially universal donors. These eliminate the need for harsh immunosuppressant drugs.

“The goal is to create a piece of liver tissue that you can use as an alternative to transplant, specifically for acute liver failure,” explains Adam Feinberg, the project’s lead researcher. These patches aren’t permanent replacements but temporary bridges, allowing damaged livers to heal while providing crucial metabolic support. Previous work with the FRESH technology successfully created pancreatic tissue for diabetes research, proving the platform’s versatility beyond liver applications.

Reality Check on Timeline and Expectations

Five years until human trials means this breakthrough needs patience alongside excitement.

Before you start planning your liver-friendly weekend in Vegas, understand the timeline. Adult-scale pre-clinical testing won’t begin for five years. Human trials follow later. The team—spanning Carnegie Mellon, University of Washington, Mayo Clinic, and other major institutions—faces significant scaling challenges.

Current patches work in lab conditions. Creating tissue robust enough for surgical implantation requires extensive validation. Each printed patch must demonstrate consistent cell viability, proper vascularization, and sustained metabolic function under physiological stress.

Market Impact Could Reshape Transplant Medicine

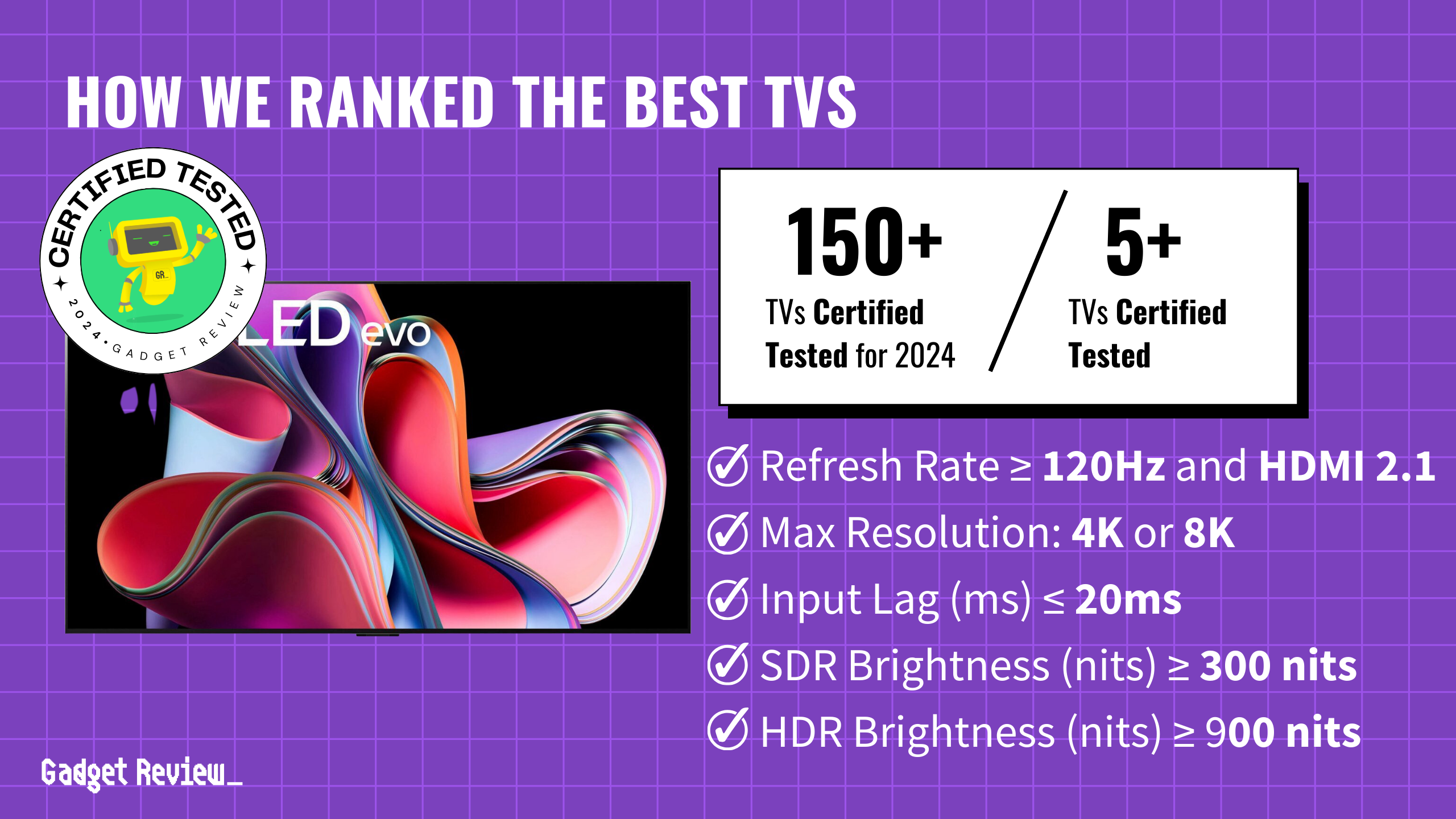

ARPA-H’s $176.8 million investment signals government confidence in bioprinting’s future.

This isn’t just academic research—it’s part of ARPA-H’s massive $176.8 million PRINT program targeting on-demand organ creation. “Developing universally matched organs will save countless lives,” notes ARPA-H Director Alicia Jackson, highlighting the government’s serious commitment to bioprinting technology.

Success here opens doors to printed heart, kidney, and pancreatic tissue, potentially disrupting the entire transplant market. Rather than racing against organ availability, patients could receive biomedical engineering tissue designed specifically for their recovery needs—a shift from scarcity-based medicine to engineered solutions.