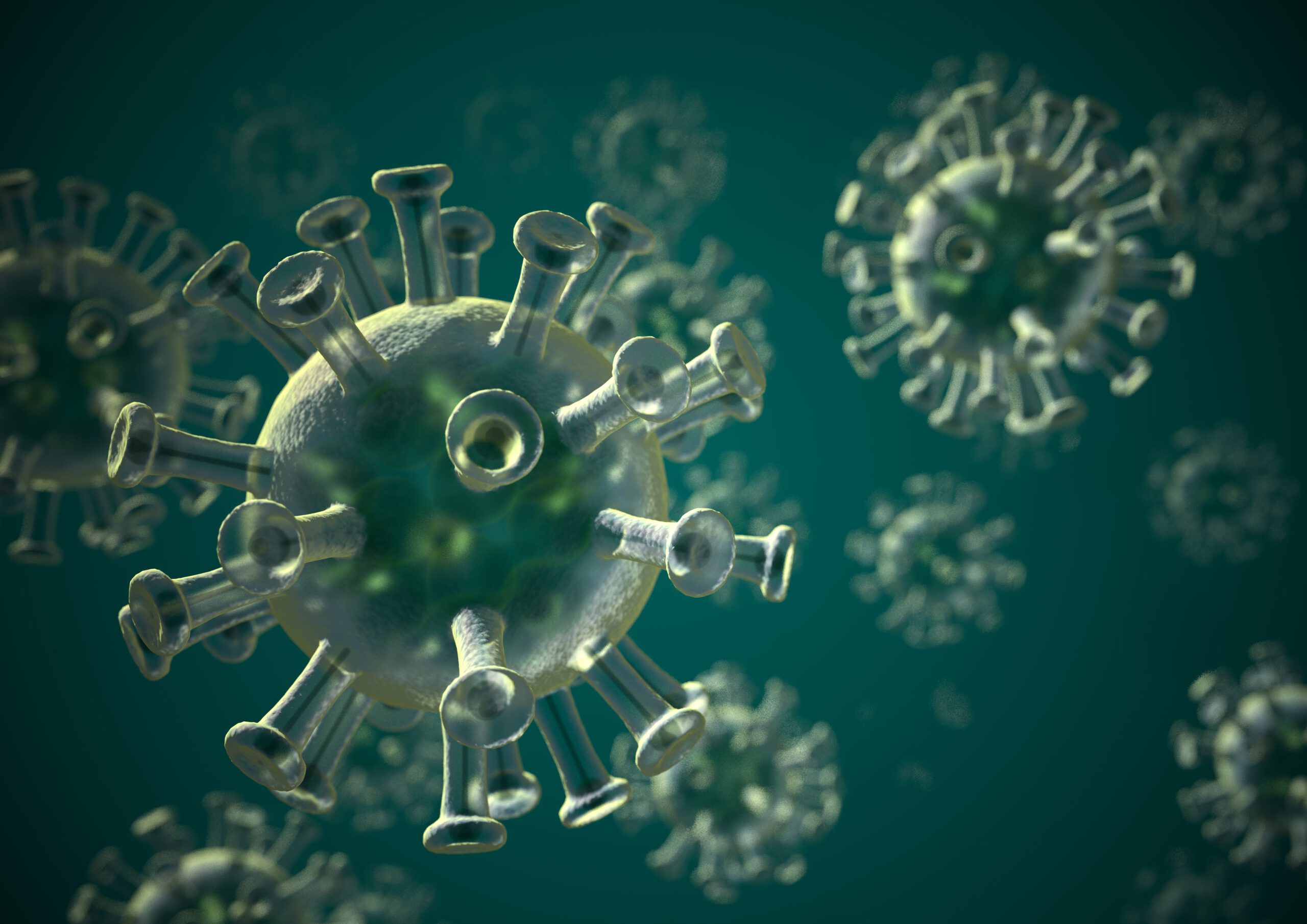

Scientists aboard the International Space Station discovered that bacterial-phage evolution follows fundamentally different pathways in microgravity, with space-evolved phages gaining enhanced infectivity against antibiotic-resistant pathogens that plague hospitals worldwide.

When Gravity Stops, Evolution Changes Course

Without gravity’s constant mixing, bacterial infections that normally take 20-30 minutes on Earth stretched to over four hours in space. The culprit? Microgravity eliminates natural convection—the invisible churning that helps viruses bump into their bacterial targets. Instead of gravity-driven mixing, space-bound microbes relied solely on molecular diffusion, like waiting for sugar to dissolve in perfectly still coffee.

This delay didn’t just slow infections; it completely rewrote evolutionary rules. Productive viral infection took 23 days to establish, creating unprecedented selective pressure that pushed both phages and bacteria toward entirely different survival strategies.

Space Viruses Develop Superior Attack Skills

T7 phages responded to their low-mixing environment by supercharging their ability to bind bacterial surface receptors. Genes controlling receptor attachment—specifically gp7.3, gp11, and gp12—mutated at accelerated rates compared to Earth controls. Meanwhile, bacteria evolved countermeasures by tweaking stress response systems and nutrient transport mechanisms.

The result resembled an arms race in slow motion, with each side adapting to constraints that don’t exist terrestrially. Deep genetic analysis confirmed this divergence: variants that thrived in orbit performed poorly back on Earth, while Earth-evolved phages showed no advantage in space.

Accidental Medical Breakthrough Emerges

The real surprise came when researchers tested their space-evolved phages against uropathogenic E. coli—bacteria responsible for stubborn urinary tract infections. These space-adapted variants produced larger infection zones and higher killing efficiency against antibiotic-resistant strains that normally shrug off wild-type T7 phages.

“This was a serendipitous finding,” said study lead Srivatsan Raman from the University of Wisconsin–Madison. The enhanced infectivity suggests that evolution under constrained conditions can accidentally generate therapeutic properties useful for terrestrial medicine.

Implications Beyond Earth’s Atmosphere

This PLOS Biology study creates a roadmap for developing better antibacterial treatments without expensive orbital experiments. By observing how viruses adapt under controlled conditions, researchers can identify specific genetic modifications that enhance therapeutic potential. The findings also inform medical protocols for Mars missions, where crew members might encounter evolved pathogens during extended spaceflight.