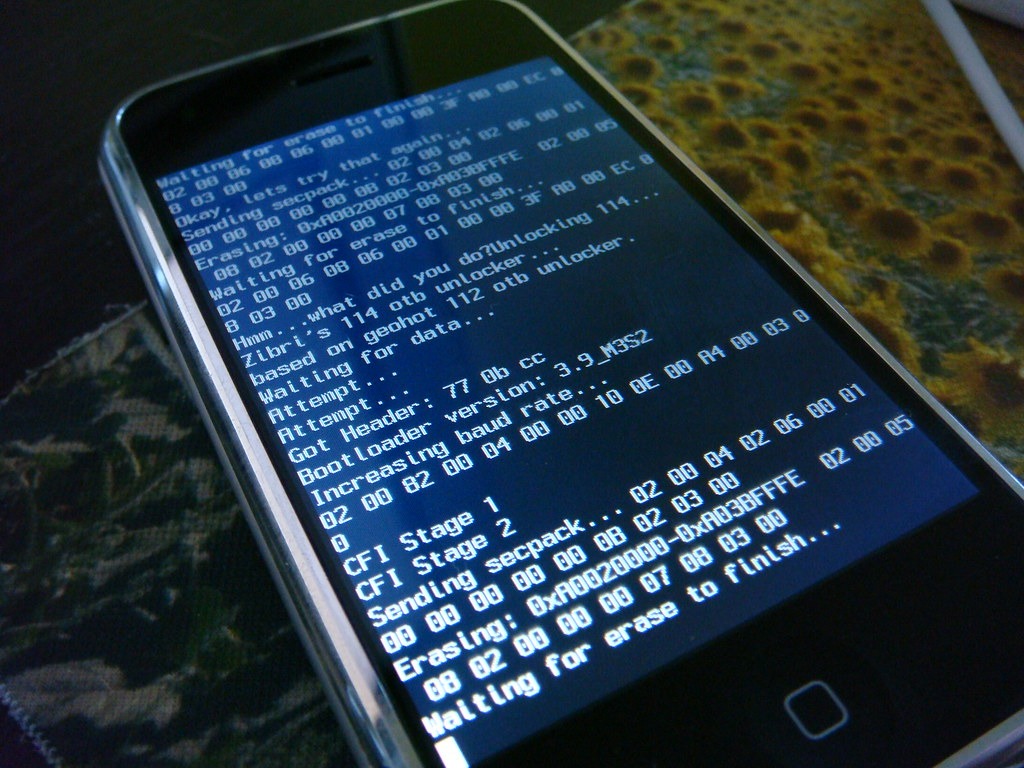

That 3 AM walk your Apple Watch recorded? It could become courtroom evidence you never intended to create. Your fitness tracker isn’t just monitoring steps—it’s building a minute-by-minute digital testimony that prosecutors, personal injury lawyers, and insurance companies can subpoena. The granular biometric and location data syncing to manufacturer clouds has transformed your wrist into a potential witness.

When Fitness Data Becomes Criminal Evidence

Murder cases now hinge on heart rate logs and GPS timestamps from wearables.

Criminal defendants are discovering their wearables make unreliable allies. In the Dabate murder case, a suspect’s timeline crumbled when his wife’s Fitbit showed her moving well after the time he claimed she was killed. An Apple Watch in Australia pinpointed a victim’s exact death window, contradicting the suspect’s account entirely.

Your device records GPS coordinates, movement patterns, heart rate spikes, and sleep disruption with forensic precision. These digital breadcrumbs create evidence more detailed than your browsing history. Unlike deleted texts, this data automatically syncs to manufacturer servers where companies retain it for extended periods under their data policies.

The Legal Discovery Process Is Surprisingly Simple

Courts approve smartwatch data requests when they meet basic relevance standards.

Federal courts apply the “narrow, proportional, and relevant” standard when evaluating discovery requests for wearable data. Personal injury lawsuits increasingly subpoena activity logs to prove or disprove disability claims—your step count either supports your injury narrative or destroys it.

Traffic accident cases use GPS data to establish whether you were walking, driving, or stopped during critical moments. Manufacturers like Apple and Garmin explicitly state in their privacy policies that they’ll comply with lawful requests, regardless of your preferences. The third-party doctrine means data you’ve shared with cloud providers enjoys weaker privacy protections than information stored on your locked phone.

Protecting Yourself From Your Own Device

Strategic privacy settings can limit your legal exposure without killing functionality.

- Review your companion app’s privacy settings to minimize what syncs to the cloud

- Enable device-level encryption and strong authentication on both your watch and smartphone

- Treat your smartwatch data like financial records—assume it could someday be scrutinized by strangers with legal authority

- Limit third-party app permissions and understand your manufacturer’s data retention policies before that information becomes discoverable evidence

- Consider which health metrics truly need cloud backup versus local storage only

The judicial system’s reliance on wearable data will only intensify as adoption climbs—over 34% of adults now wear fitness trackers daily. Your smartwatch promised to improve your health, but understanding its legal implications might be the most important wellness insight it provides.