The 1970s was a decade of ambitious tech dreams and spectacular commercial face-plants. From video phones that cost more than cars to instant movie cameras that delivered home videos worse than security footage, the polyester decade was lousy with “futures” that never bothered to show up for most of us. These hand-picked spectacular failures promised big but delivered something else entirely—expensive lessons in what happens when innovation runs headfirst into reality.

10. AT&T Picturephone

The future of communication came with a mortgage-sized monthly payment.

Some called it the future, but its launch price was a solid “nope” for most: $160 a month. That’s over $1,200 in today’s cash, which means a year of Picturephone cost more than your first car—and probably delivered fewer thrills. Early adopters dealt with dedicated wiring, a clunky design, and an unflattering camera angle, giving new meaning to “bad hair day.”

This cautionary tale proves that sometimes, the best tech is the one that doesn’t require a second mortgage or a Zoom-worthy makeover.

9. Polaroid Polavision

Instant movies that made family videos look like abstract art.

Polaroid’s Polavision promised instant movie magic with its instant movie camera, but the reality? Not quite the Kodak moment they advertised. The whole setup was bulky and awkward, like lugging around a Betamax player just to film a 3-minute clip. And let’s not forget the high price tag—you could’ve bought a decent used car for what this thing cost.

The grainy, soundless footage was about as watchable as a cat video from 2007. Polaroid overshot their tech capabilities, thinking they could pull off Spielberg when they delivered more of a Blair Witch Project vibe.

8. Sony U-matic Video Cassette

The professional-grade system that priced itself out of homes.

Sony dropped the U-matic Video Cassette, the first widely available video cassette system in 1971. Problem was, those early machines were bulkier than a Kardashian’s luggage and cost more than a semester at Harvard. Recording time was tight, so naturally, it found a niche in pro and education sectors.

While U-matic was flexing its muscles, VHS and Betamax were gearing up for the main event. Cheaper and more practical, VHS and Betamax became the go-to, leaving U-matic as a pricey stepping stone.

7. Cartrivision

Netflix’s awkward ancestor that couldn’t figure out how to work.

Cartrivision, the first home video system with rental cartridges, aimed high but face-planted hard. The issue? The process was so unclear even your grandma would throw her hands up. With limited titles and expensive machines, this noble failure quickly bit the dust.

Add in tape degradation and overcomplicated setup, and it’s clear why even the most enthusiastic couch potatoes gave it a hard pass. It’s like trying to assemble IKEA furniture with oven mitts—a bold, doomed experiment in home entertainment.

6. LaserDisc

Cinema quality that demanded cinema prices for everything.

LaserDisc promised cinema-quality video and superior audio, but the gear was hardly Netflix-and-chill. Between the pricey players and the large, fragile discs, your wallet and shelves both felt the squeeze. While VHS tapes let you record TV shows like a caveman’s DVR, LaserDiscs offered zero recording capability.

You could only watch what studios sold, with limited titles at premium prices. LaserDisc demanded you pay cinema prices for the privilege of owning a fragile disc that took up half your shelf.

5. Quadraphonic Sound Systems

Four-channel chaos that made compatibility a dirty word.

Big brands like Sansui and RCA jumped into the 4-channel fray, but then came the format wars—QS, SQ, CD4. “Compatibility” became a four-letter word, ensuring your expensive amp and speaker setup was only good for specially encoded albums.

The innovation was there, but it was like ordering a pizza that needs its own hazmat team to assemble. Quadrophonic sound proved that sometimes, being ahead of the curve just means getting sliced and diced by it.

4. TV Typewriter

The home computer that made typing feel like punishment.

The TV Typewriter tried to bring computing home by allowing users to input text—think tweets but on a cathode-ray tube—then display it on television screens. For families dreaming of ditching typewriters for digital, this seemed promising.

Lacking processing power, storage, or easy-to-use software, it was about as practical as using a rotary phone to order Uber. Despite its flop, the TV Typewriter helped spark the home-computing revolution—proving even the weirdest ideas can leave a mark.

3. Ford Pinto Tech Features

Futuristic dashboard that came with explosive side effects.

The Pinto‘s interior felt like stepping into a low-budget spaceship, complete with digital-style clocks and warning lights that flickered like a dodgy TikTok filter. Its early stereo systems blasted tunes perfectly, as long as you didn’t mind the occasional malfunction.

Despite the shiny gadgets, the Pinto became less about innovation and more about ignition—for all the wrong reasons. Any tech dreams it sparked were quickly extinguished by its fuel tank’s uncanny knack for rupturing in rear-end collisions.

2. Early Electronic News Gathering (ENG) Cameras

Portable news cameras that redefined “portable” very generously.

ENG cameras were designed to let field reporters broadcast without film processing delays. The only problem? These early models were about as portable as a fridge strapped to a unicycle, weighing more than your average defensive lineman.

News crews chasing breaking stories got slowed down by long setup times and heavy batteries that died faster than a meme’s lifespan. Despite their limitations, these cumbersome cameras laid the groundwork for today’s sleek, mobile broadcast tech.

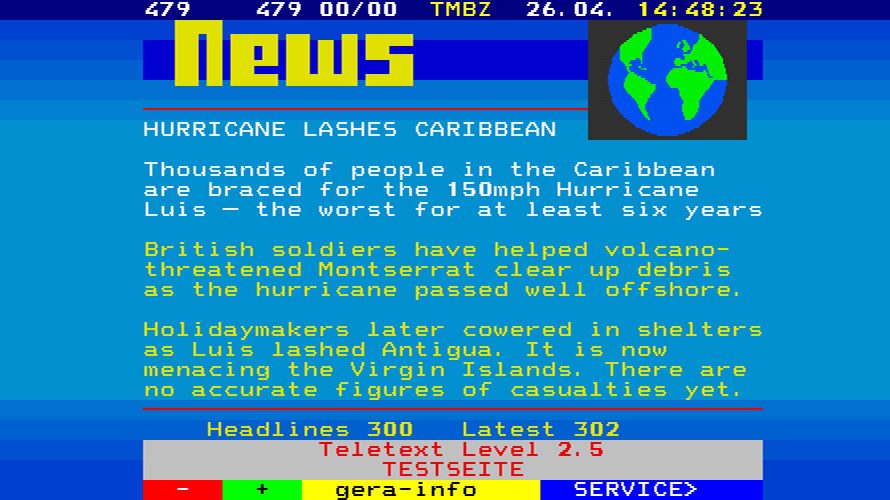

1. Teletext

Digital information delivery that made dial-up look speedy.

Teletext aimed to deliver digital information—news, weather, stock updates—through television screens using specialized decoders. The slow transmission speeds made waiting for headlines feel like watching paint dry, with grainy weather maps taking forever to materialize.

Its visionary approach was clear, but limited content and sloth-like pace relegated it to a technological footnote—a beta version of the internet played out on your TV screen that nobody had the patience to actually use.