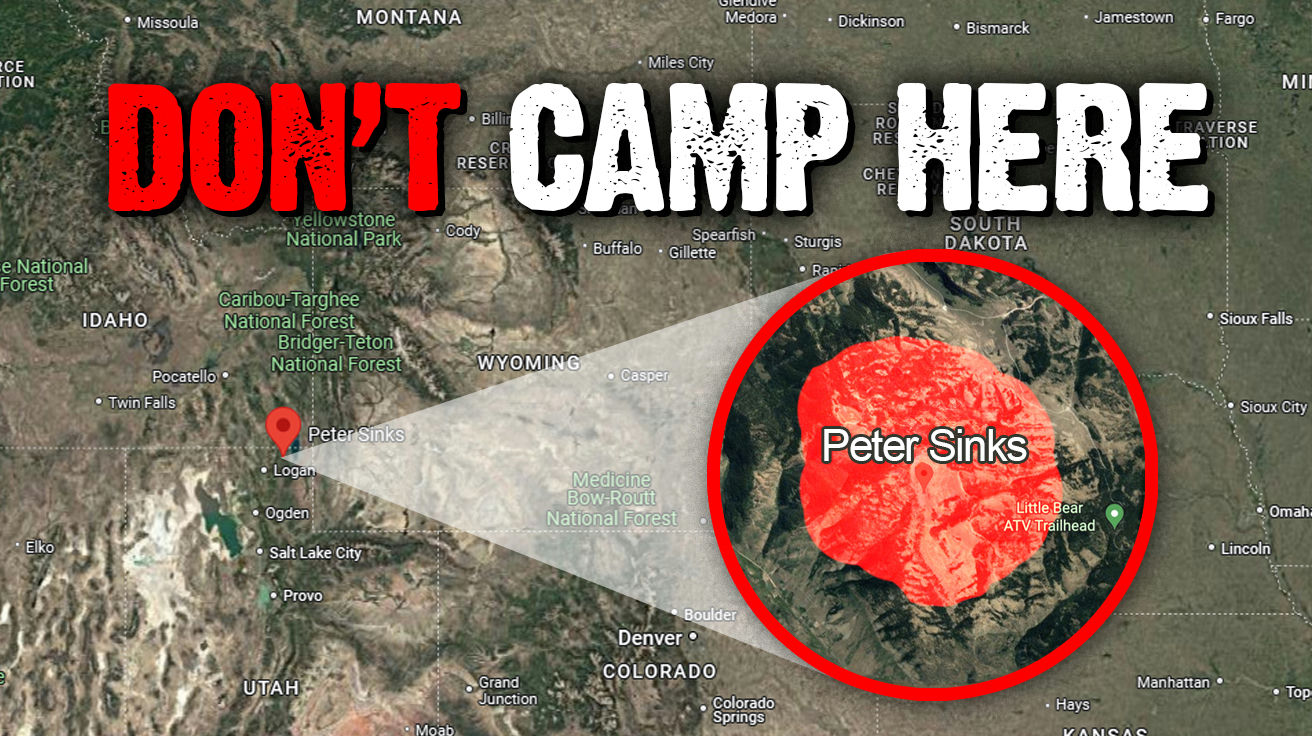

Venture into the Logan, Utah, area, where a peculiar natural wonder defies expectations. Peter Sinks, a sinkhole nestled in the Bear River Mountains, consistently records temperatures that make even Arctic explorers shiver. This geological depression becomes colder than Alaska during winter nights. The unique bowl-like geography traps frigid air, creating astonishing temperature inversions that puzzle even experienced meteorologists. Why would this unassuming hollow be colder than areas at higher elevations or northern latitudes? Understanding Peter Sinks illuminates the fascinating interplay between geography and climate.

Disclaimer: Some images used for commentary and educational purposes under fair use. All rights remain with their respective owners.

Location and Basic Facts

You might easily miss it while hiking the towering peaks of northeastern Utah. Peter Sinks sits inconspicuously in the Bear River Mountains, resembling an ordinary depression spanning about a half-mile across. Nothing about its appearance suggests extremity.

At approximately 8,164 feet elevation, it seems unremarkable compared to many higher mountain locations. But appearances deceive. This humble hollow routinely ranks as the coldest spot in the contiguous United States. Year after year, this hidden basin experiences temperature plunges that dramatically outpace surrounding areas, making its discovery all the more surprising for visitors.

Record-Breaking Cold

The thermometer told an almost unbelievable story on February 1st, 1985. Peter Sinks recorded a bone-chilling -69.3°F, marking the second-coldest temperature ever documented in the lower 48 states. This reading came within a half-degree of the all-time record set in Montana.

Just a few hundred yards away at the rim, temperatures can be up to 70°F warmer than at the basin’s bottom. Talk about microclimate extremes! At these temperatures, exposed skin freezes in seconds, and common materials become brittle enough to shatter upon impact. It’s as if Mother Nature decided to create her own walk-in freezer, right in the middle of Utah.

Geological Formation as a Cold Air Lake

This limestone sinkhole creates perfect conditions for what meteorologists call a “cold air lake.” Over thousands of years, the dissolution of limestone has gradually deepened this depression. The process resembles carving out a giant natural bowl—except instead of soup, it collects some of the coldest air on the continent.

The mechanics work with brutal simplicity: cold air weighs more than warm air. Unlike most valleys that allow air to flow through, this geological depression has no outlet. The bowl shape collects frigid air that has nowhere to escape. During still winter nights, the resulting cold air pool becomes increasingly concentrated—creating a natural refrigerator unlike almost any other in North America.

Limestone Drainage System

The underlying geology maintains Peter Sinks’ extreme climate through a clever trick. Limestone dissolves when exposed to even slightly acidic water, creating a network of underground channels throughout the rock. Water readily seeps through this porous material and disappears underground.

Meanwhile, the heavy cold air remains firmly trapped within the depression. No escape hatch exists for the frigid temperatures. This geological feature provides climate scientists with a perfect natural laboratory for studying extreme conditions. Their findings improve weather prediction models affecting everything from agriculture to infrastructure development throughout surrounding regions.

Utah Climate Center Monitoring

Since 2009, the Utah Climate Center has maintained comprehensive monitoring of this fascinating phenomenon. Two weather stations—one at the sink’s bottom and another near the rim—continuously track temperature differentials while monitoring wind patterns.

The most extreme cold emerges on cloudless, still nights when nothing disturbs the natural temperature stratification. It’s meteorological theater at its finest. Through years of data collection, scientists have mapped fascinating patterns in how these cold air pools form and dissipate. Their research contributes valuable insights for meteorologists worldwide studying similar microclimates—knowledge that ripples outward to improve our understanding of atmospheric behaviors everywhere.

Reverse Tree Line

The vegetation around Peter Sinks tells a revealing story even casual visitors can read. Trees grow progressively smaller as you descend toward the basin, eventually disappearing completely at the bottom—a phenomenon known as “reverse tree line.”

In most mountain settings, you’d expect the opposite: trees disappear as you climb higher. Here, extreme cold creates conditions too harsh for trees to survive at the bottom. With fewer than 4 frost-free days annually, sustained plant growth becomes nearly impossible. Only the hardiest alpine flora survives here. It’s like finding arctic conditions in an unexpected pocket of Utah—a botanical transition zone that provides striking evidence of nature’s most extreme microclimates.

Other Sinkholes in the Area

Peter Sinks isn’t the only show in town. Several similar depressions dot the surrounding landscape. South, Middle, and North Sinks lie much closer to Highway 89, making them considerably more accessible. Highway 89 actually runs directly through North Sink’s center—offering a drive-by geology lesson for anyone passing through.

These neighboring sinkholes typically remain 10-15°F warmer than Peter Sinks due to different dimensions and air disturbances from nearby traffic. Think of them as Peter’s slightly more temperate cousins. Their accessibility makes them valuable comparative sites for researchers studying these unique microclimates. Together, they form a natural laboratory complex that helps scientists refine their understanding of cold air pooling phenomena—a meteorological mystery hiding in plain sight along a Utah highway.