Pancreatic cancer kills faster than any other major cancer, but Spanish researchers just achieved something nearly impossible: complete tumor elimination with no relapse.

Your chances of surviving pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma remain brutally slim—under 10% make it five years. This cancer resists almost everything doctors throw at it, spreading silently until it’s too late. But researchers at Spain’s National Cancer Research Centre just published results in PNAS that sound too good to be true: they completely eliminated pancreatic tumors in three different mouse models, with zero relapse during extended follow-up.

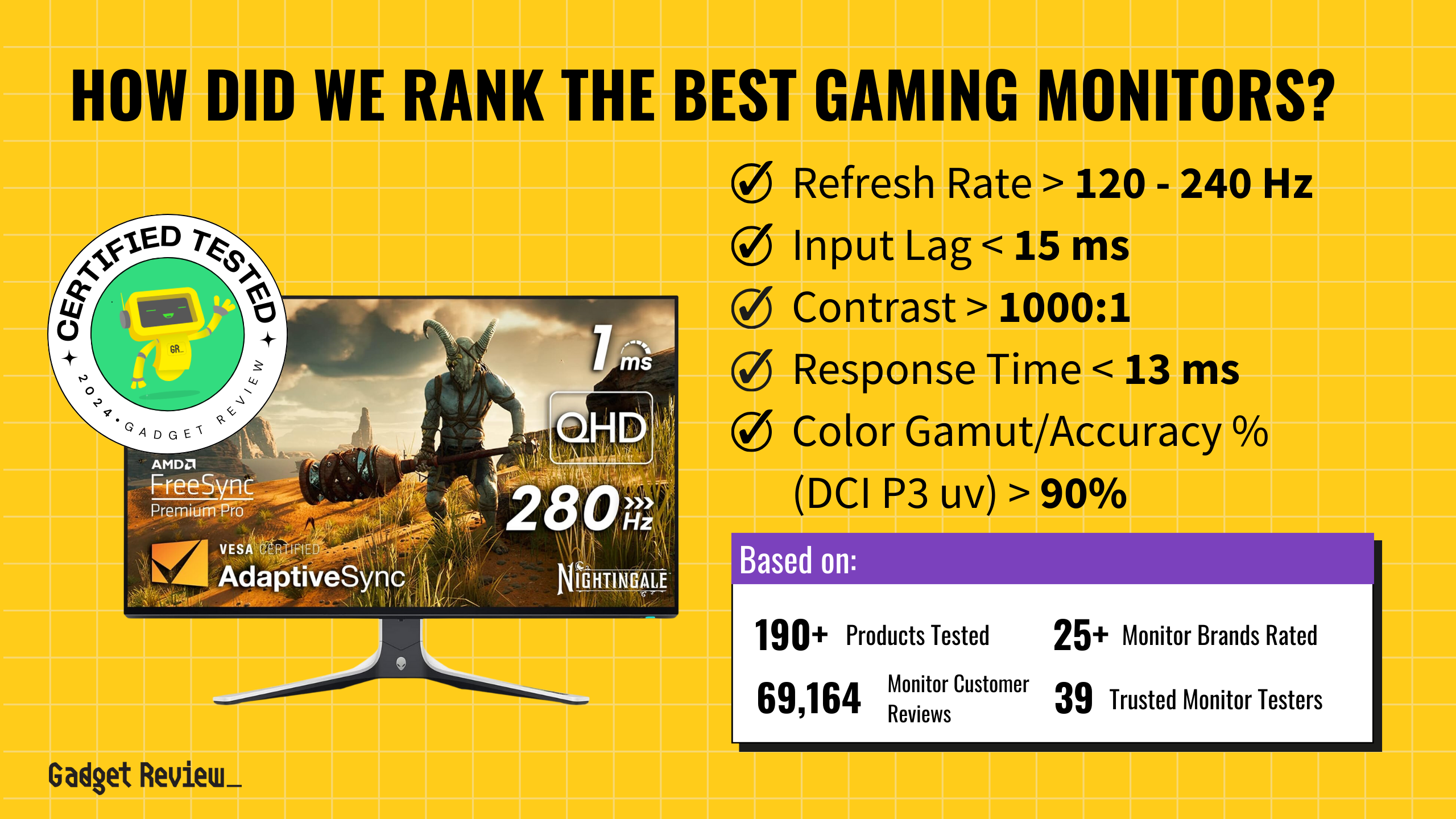

The Three-Pronged Attack Strategy

Researchers targeted multiple points in the cancer’s most critical pathway simultaneously.

The breakthrough centers on KRAS, a protein that drives roughly 90% of pancreatic cancers but has long been considered “undruggable.” Instead of targeting KRAS alone—which cancer cells quickly outmaneuver—Mariano Barbacid’s team hit three different points in the same pathway.

They combined:

- An experimental KRAS inhibitor

- An approved lung cancer drug targeting EGFR/HER2 pathways

- A STAT3 protein degrader

Think of it like cutting internet, power, and phone lines to the same building—cancer can’t adapt when you attack everything at once.

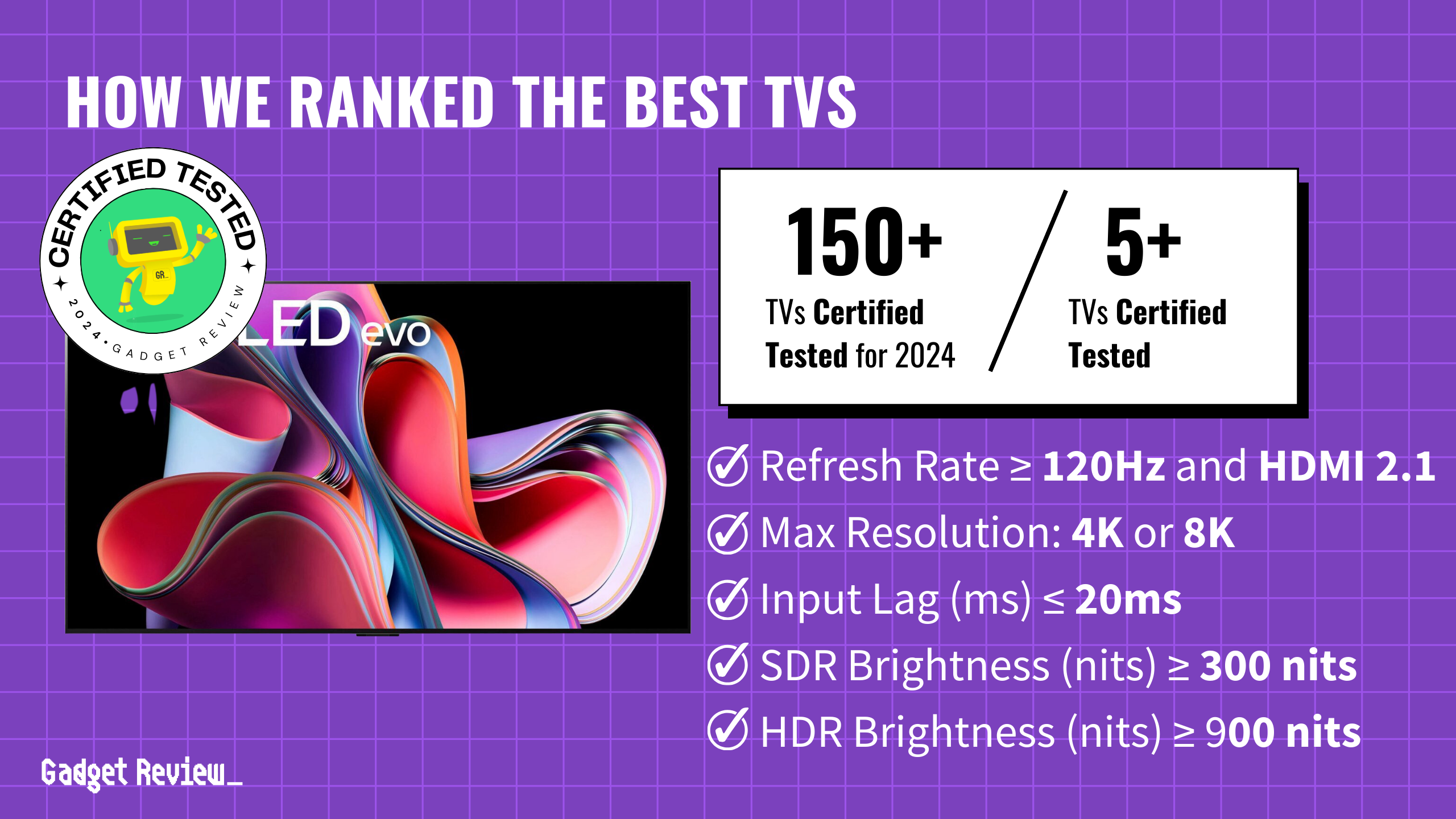

Complete Elimination, Minimal Side Effects

The results surpassed typical cancer research expectations.

Cancer research rarely delivers fairy tale endings, especially with pancreatic tumors. Yet all three mouse models showed complete tumor regression with minimal toxicity—results that would make any oncologist do a double-take.

The mice stayed cancer-free throughout extended monitoring periods, something that doesn’t happen often in this field. For context, current pancreatic cancer treatments might shrink tumors temporarily, but they almost never eliminate them entirely.

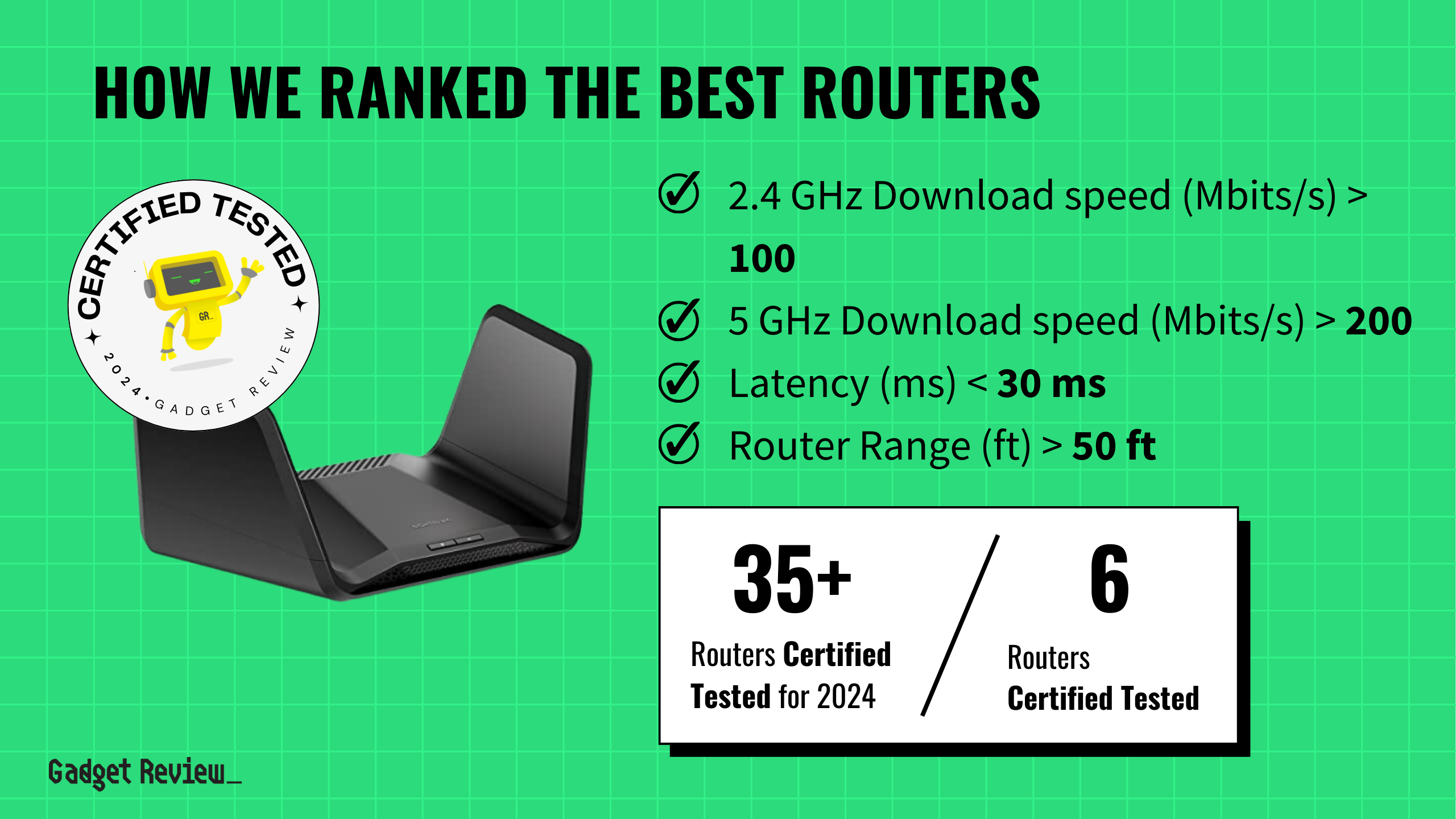

The Reality Check You Need to Hear

Mouse studies don’t automatically translate to human success.

Before you start planning celebrations, remember we’re talking about mice, not humans. Cancer research graveyards are littered with promising mouse studies that failed spectacularly in people. The three-drug combination needs extensive optimization before human trials can even begin.

Complex drug interactions, dosing schedules, and human biology could derail everything. Still, the CNIO authors remain cautiously optimistic: “These studies open a way to design new combination therapies that can improve the survival of patients.”

Why This Matters for Future Treatment

The approach could reshape how doctors attack resistant cancers.

This research validates a new strategic direction: overwhelming cancer’s escape routes instead of blocking just one pathway. With over 10,300 pancreatic cancer cases annually in Spain alone, and similar devastation worldwide, any genuine progress matters enormously.

The combination approach could eventually integrate with existing chemotherapy regimens or emerging immunotherapies. Whether it works in humans remains unknown, but it offers something pancreatic cancer patients desperately need—a genuinely different way to fight back.