History books sell sanitized narratives about ancient civilizations. Museums display artifacts behind glass with clinical placards that drain all life from objects once central to human experience. What these institutions rarely mention is how many “discoveries” involve questionable attribution, colonial exploitation, or outright theft.

Think of these artifacts as ancient flash drives — storage devices containing civilization’s source code. Each item on this list peels back layers of conventional wisdom about the past. Some reveal sophisticated technologies that challenge modern smugness about “primitive” ancestors. Others expose how academic institutions perpetuate myths to maintain their authority as gatekeepers of historical truth.

22. Bison of Tuc d’Audoubert

These 15,000-year-old clay bison sculptures, discovered in 1912, expose archaeology’s awkward secret — experts frequently mangle basic facts. The cave name “Tuc d’Audoubert” gets butchered in translations like subtitles in a poorly dubbed foreign film. Even professional publications contain inconsistencies that would never fly in other scientific disciplines.

The nearby children’s footprints suggest these spaces served purposes beyond the “shamanic ritual” explanation archaeology defaulted to for decades. Like attributing everything unusual to “aliens” on fringe history shows, professional archaeologists have their own intellectual shortcuts. The presence of children challenges the narrative of isolated male shamans creating cave art in religious ecstasy. These sculptures might instead represent educational spaces where skills were passed down — ancient classrooms that upend romantic notions about prehistoric art creation.

21. Ancient Hebrew Manuscript

This leather manuscript, intercepted by Turkish police in 2019, spotlights archaeology’s shadowy underbelly — the black market artifact trade that continues to flourish despite international agreements. Like drugs and weapons, ancient objects move through underground networks that connect looters to wealthy collectors willing to pay premium prices for historical contraband.

The 16-page document with bird illustrations represents thousands of similar items extracted without scientific documentation or cultural permission. The red hexagonal stone decorating its cover might contain contextual clues forever lost when it was removed from its original location. Museums showcase their legitimate acquisitions while an invisible parallel market operates in the shadows. This underground economy destroys archaeological contexts as effectively as a delete key erases computer files, leaving permanent gaps in human knowledge that no future technology can restore.

20. Figurines from Golan Heights

When archaeologists announced that tiny carved figures had been discovered in October 2020, they buried the political context deeper than the artifacts themselves. These supposedly ancient moon-worship relics emerged from contested territory that’s been a geopolitical flashpoint for decades. The archaeological equivalent of finding evidence in a crime scene that’s been compromised.

Dating these figurines to 3,000 years ago serves convenient political narratives about historical connections to land. Archaeology has never operated in a political vacuum. Ancient artifacts become modern propaganda tools faster than you can say “national heritage.” The horned designs might symbolize lunar worship, but they also represent how historical objects become weaponized in contemporary conflicts. Speaking of weapons, here are a few that rewrote history.

19. Pyrgi Gold Tablets

These 2,500-year-old inscribed gold tablets showcase what mainstream historians rarely emphasize — ancient Mediterranean cultures maintained sophisticated international networks long before social media connected teenagers across continents. Found in 1964 at an Italian port, they feature parallel text in two languages, like finding an ancient version of Google Translate.

The tablets document religious dedications, but museum placards typically downplay their most significant feature. These artifacts demolish the neat categories historians love to impose on the past. The inscription to goddess Astarte by an Etruscan ruler named Thefarie Velianas reveals how cultural boundaries were as fluid in 500 BCE as they are in today’s globalized world. This inconvenient messiness complicates the clean historical narratives preferred by academic departments seeking funding and publishing deals.

18. Lamashtu Plaque

This 2,800-year-old bronze plaque designed to ward off a disease-causing demoness reveals what museum placards rarely acknowledge — ancient people weren’t stupid about healthcare, just working with different operating systems. Their supernatural explanations may seem primitive to modern scientific minds, but their practical responses were often sophisticated.

While contemporary medicine relies on antibiotics, ancient Assyrians developed psychological infrastructure against illness. They created tangible objects that gave people a sense of control amid invisible threats — not unlike how modern societies cling to protective rituals during pandemics. The Lamashtu plaque represents an early form of cognitive behavioral therapy wrapped in supernatural packaging. Ancient solutions to universal human problems often contained practical wisdom that gets dismissed because of their mystical packaging.

17. Viking Game Pieces

These gaming artifacts expose how historical narratives get manipulated to serve contemporary agendas. Vikings have been recast from brutal raiders to chess-playing intellectuals as easily as characters get rebooted in Hollywood franchises. The hnefatafl game pieces crafted from bone and stone reveal a culture with recreational pastimes beyond the rape and pillage emphasized in historical accounts.

The evolution from stone to whale bone pieces tracks technological adaptation but raises questions about historical whitewashing. Academic institutions selectively highlight civilized aspects of cultures that align with modern values while downplaying uncomfortable truths. Like social media profiles that present curated versions of reality, museum exhibits construct sanitized narratives of the past. These gaming pieces demonstrate Viking strategic thinking, but the selective emphasis reveals more about our own cultural priorities than objective historical understanding.

16. Tuxtla Statuette

The 1902 discovery near Mexico’s Tuxtla Mountains exposes archaeology’s identity crisis. Experts can’t even agree on basic facts about this figurine. The mainstream archaeological establishment labels it “Epi-Olmec” — a classification that sounds authoritative until you realize it’s like calling something “sort-of iPhone-ish” without understanding its operating system.

Most significantly, this figure contains undeciphered Isthmian writing that academics have failed to crack despite a century of trying. The archaeological establishment doesn’t advertise its failures. The untranslated symbols represent thousands of lost stories from civilizations erased by colonization. Like a corrupted hard drive from a civilization that left no recovery password, these inscriptions remind us how much knowledge has been permanently deleted from human history while experts build careers claiming authoritative understanding.

15. Hallaton Helmet

This Roman cavalry helmet exposes how archaeological findings get filtered through confirmation bias. Found in an Iron Age shrine, it suggests Romans collaborated with locals they supposedly conquered. This contradicts the neat imperial expansion narrative taught in schools, where Romans simply steamrolled “barbarian” populations like bulldozers clearing construction sites.

The established historical account resembles a simplistic sports broadcast where Rome always wins. The reality was messier. This helmet’s hybrid cultural features reveal complex relationships between Romans and Britons that don’t fit into convenient categories of conqueror and conquered. Archaeological institutions prefer cleanly divided historical periods that can be sorted into separate museum wings and funding categories, even when evidence suggests messy cultural exchanges that defy simple classification.

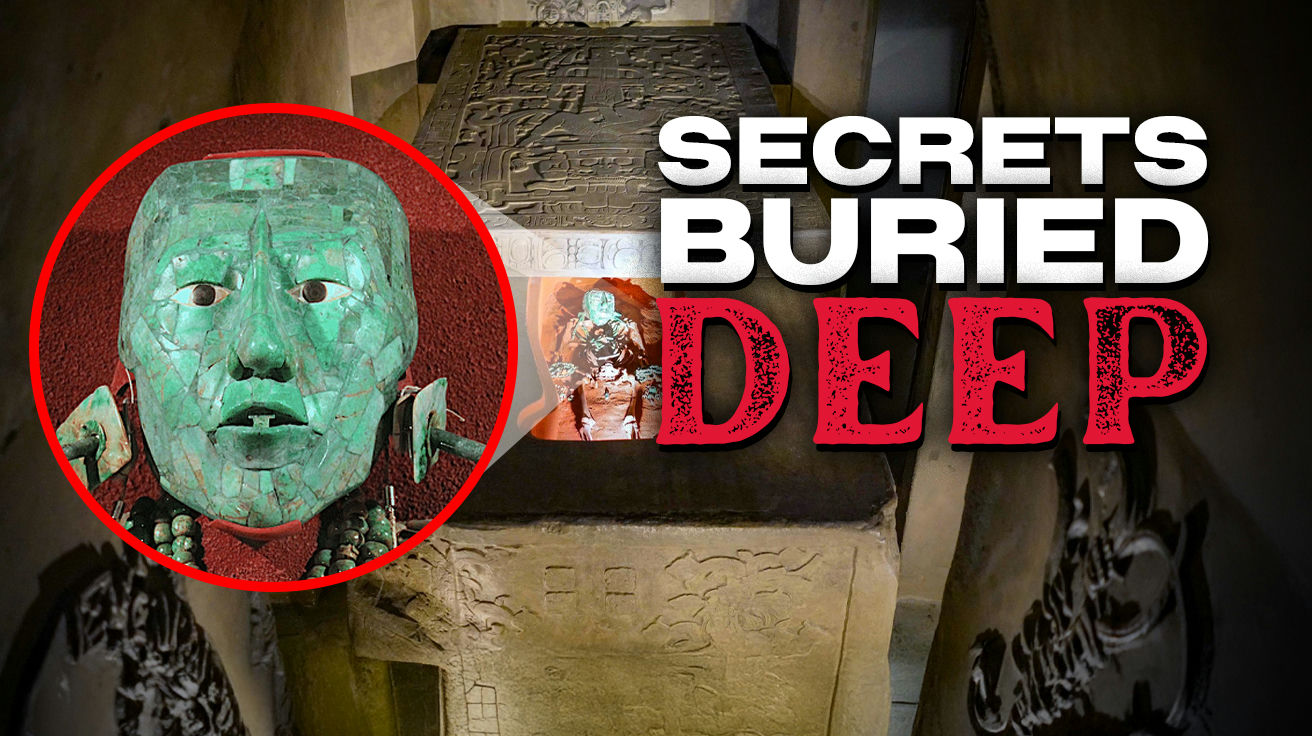

14. Mask of K’inich Janaab’ Pakal

Academic journals celebrate this Mayan ruler’s 68-year reign while glossing over a crucial detail — the mask discovered at Palenque doesn’t match official accounts. Like a plot hole in a Marvel movie, the discovery timeline contains contradictions that respected institutions ignore.

The establishment version claims this mask was found in the mid-20th century, yet search for primary sources and you’ll hit academic quicksand. Mainstream archaeologists have built careers on certain interpretations of Mayan artifacts. Questioning these narratives threatens not just reputations but entire departmental funding streams. Meanwhile, indigenous perspectives on their own cultural heritage remain sidelined in favor of Western interpretations that serve institutional interests.

13. War Helmet of Meskalamdug

Mainstream archaeology presents this 4,500-year-old gold helmet as belonging to Meskalamdug of Ur, yet the attribution contains more speculation than a cryptocurrency investment seminar. Ancient objects often get linked to famous rulers through evidence that wouldn’t hold up in traffic court, let alone scientific inquiry.

Leonard Woolley’s 1924 discovery fits a troubling pattern in archaeological history. Western archaeologists removed countless treasures from their original contexts during the colonial era, separating objects from their cultural landscapes like taking screenshots of single frames from feature films. The gold design reveals extraordinary craftsmanship, but museum visitors rarely learn about the ethically questionable methods through which many spectacular finds reached Western institutions. This uncomfortable history gets minimized in informational placards that emphasize artistic significance over acquisition ethics.

12. Ancient Dacian Helmet

While museums trumpet this 2,000-year-old Romanian discovery as a “ceremonial” piece, they’re burying the lead. Archaeologists claim it belonged to nobility because it lacks practical features like eyeholes. This explanation resembles the infamous line from The Emperor’s New Clothes — “only the sophisticated can appreciate it.”

The inconvenient truth? Many so-called “ceremonial” classifications simply mean experts can’t figure out an artifact’s actual function. The helmet’s thick gold sheets suggest value systems utterly different from our own. While modern defense budgets funnel billions into stealth bombers, ancient Dacians invested their resources in objects that connected leadership to cosmic forces. The stark contrast reveals how thoroughly capitalism has rewired human priorities.

11. Thornbury Hoard

While you stress about your 401k, consider Ken Allen who just wanted a backyard pond in 2004 and instead unearthed11,460 ancient copper coins. This accidental discovery reveals more about Roman economic anxiety than most history textbooks. Minted between 260-348 CE, these weren’t fancy gold sovereigns but everyday coins – the ancient equivalent of hoarding quarters during economic uncertainty.

The timing of this stash speaks volumes – hidden during the Roman Empire’s third-century crisis when inflation ran rampant and currency devaluation was imperial policy. Economic historians get misty-eyed over finds like this because they reveal actual behavior during financial panic, not just official records. It’s similar to stumbling across someone’s extreme couponing stash from the 2008 recession – a raw snapshot of how regular people responded to economic instability. What museum plaques won’t mention: this hoard represents someone’s hedge against catastrophe that never got reclaimed.

10. Golden Death Mask Of Tutankhamun

What if the most famous archaeological find in history is actually ancient Egypt’s most elaborate hand-me-down? Recent analysis suggests Boy King Tut’s iconic golden mask – the face launched onto a thousand museum gift shop tote bags – was originally created entirely for someone else. Close examination reveals ear piercings and facial proportions more consistent with a female ruler, likely Nefertiti. That’s right: archaeology’s greatest treasure appears to be history’s most expensive regift.

The hastily modified inscriptions – where “beloved of Akhenaten” awkwardly precedes Tutankhamun’s divine titles – represent ancient damage control when a teen pharaoh died unexpectedly. Museum displays rarely highlight this recycling angle because it undermines the romantic narrative of a boy king’s glorious tomb. This 11-kilogram solid gold mask with inlaid glass and gemstones wasn’t just funeral decoration – it was propaganda designed to solidify fragile political legitimacy during Egypt’s most controversial religious period. It’s essentially the ancient version of a rushed rebrand when a company faces unexpected leadership changes.

9. Cunetio Hoard

When archaeologists uncovered 54,000 coins near Wiltshire in 1978, they discovered physical evidence of an ancient financial meltdown. This massive stash, with coins primarily featuring Emperor Gallienus (253-268 CE), represents the ancient equivalent of stuffing your life savings under the mattress when banks start failing. The sheer volume suggests institutional collapse rather than personal savings.

What makes this find explosive is what the coins reveal about official propaganda versus economic reality. While imperial portraits maintained dignified expressions, the coins themselves tell a different story through progressive debasement – from 50% silver content down to sometimes less than 5%. It’s comparable to those Instagram vs. reality posts where someone’s glamorous social media presence masks financial distress. The Cunetio hoard isn’t just an archaeological curiosity; it’s spreadsheet-worthy data proving that even superpowers face economic reckoning when they print money unchecked.

8. Treasure Of Begram

Before Amazon Prime and shipping containers, the ancient Silk Road moved luxury goods across continents with surprising efficiency. The smoking gun? Over 1,000 diverse artifacts excavated from Afghanistan between 1936 and 1940 rewrite our understanding of ancient globalization. Roman glass, Chinese bronzes, and Indian ivory sitting together in a 2nd-century CE stash tell us the Kushan Empire wasn’t just some forgotten kingdom – it was essentially running ancient DHL.

The mainstream historical narrative pushing Rome and China as isolated superpowers conveniently ignores this archaeological bombshell. These artifacts show that people weren’t waiting for Marco Polo to introduce east-west trade – they were mixing cultural influences since millennia before. It’s similar to discovering your grandparents had Instagram before it was cool. The Kushan Empire operated the ancient equivalent of a free trade zone where artistic styles and manufacturing techniques from three continents converged with astonishing results.

7. Great Torque Of Snettisham

While most ancient gold sits behind glass with sanitized placards, this twisted neck ring tells a far more interesting tale. Found in 1950 by a farmer’s plow, not some tweed-jacketed academic, this 1.2-kilogram gold masterpiece rewrites what we thought possible for “primitive” Iron Age craftsmen. Dating to 75 BCE, it’s essentially the ancient equivalent of finding a Ferrari buried in your backyard.

The artifact’s connection to the Iceni tribe – the same folks whose queen Boudica later torched Roman London – rarely makes it into museum brochures. Much like the hidden sub-plot in The Usual Suspects, the real story sits in plain sight but goes unnoticed. The torque wasn’t just jewelry; it was political capital in an era when displaying wealth meant displaying power.

6. Fingington Hagg Hoard

The fancy story: decorated horse fittings and intricate scabbard mounts discovered in 19th-century Yorkshire represent high-end Celtic craftsmanship. The more interesting reality: these 1st-century items were likely hot merchandise, stolen from Roman military supplies by locals who weren’t exactly thrilled with occupation. This collection essentially documents an ancient resistance movement through its supply chain disruption.

Museum placards typically gloss over the awkward question of how native Britons acquired Roman military accessories during active occupation. It’s similar to the scene in Goodfellas where stolen goods flow freely among those “in the know” – except here it’s Roman cavalry equipment circulating among Celtic tribes. The sophisticated craftsmanship doesn’t represent peaceful cultural exchange but rather targeted theft focusing on high-value military items. These aren’t just pretty historical trinkets; they’re physical evidence of indigenous pushback against imperial control through economic sabotage.

5. Crusader Gold Coins

The 24 gold coins and single earring found in Israel in 2022 aren’t just shiny trinkets – they’re a 900-year-old emergency fund that never got retrieved. Think of them as the medieval version of stuffing cash under your mattress before evacuating for a hurricane. Except in this case, the hurricane wore chainmail and carried a cross. The hasty burial – evident from the scattered arrangement – speaks volumes about the panic when word spread that crusader armies were approaching.

What makes this find particularly juicy is the timing. These weren’t coins hidden during some random Tuesday in medieval history – they were buried precisely when European armies were turning the Levant into their personal playground in the name of religion. The single earring mixed with the coins suggests this wasn’t some royal treasury but a family’s entire net worth, hurriedly hidden as hoofbeats approached. It’s straight out of a Nolan film – complete with ticking clock and abandoned wealth.

4. Crowns Of Gaya

While K-pop and Parasite grab global headlines now, Korea’s ancient Gaya crowns reveal a cultural powerhouse that history textbooks conveniently forgot. These 5th-century gold headpieces with their distinctive tree and antler designs weren’t just fancy hats – they were walking billboards of political legitimacy for a confederation squeezed between larger kingdoms. The museum might label them “National Treasure #138,” but that sterile designation masks their true significance.

What the exhibit signage won’t mention is how these artifacts challenge the neat three-kingdoms narrative of early Korean history. The crowns blend influences from neighboring Silla and Baekje while maintaining distinct Gaya identity – kinda how hip indie bands borrow from mainstream styles while creating something entirely new. Next time someone claims ancient Korea was culturally uniform, just point them to these crowns and watch their certainty crumble.

3. Lampsacus Treasure

Forget Netflix’s Crown Jewels – the real drama sits in this Byzantine silver hoard that tells us more about power plays than any streaming series. Unearthed in 1847 in modern-day Turkey, these artifacts come from an empire history books often sideline despite lasting a millennium. The silver tripod lamp, dozen pear-shaped spoons, and ornate dishes aren’t just fancy cutlery – they’re receipts from an economy that dominated the Mediterranean.

The 6th-century dating puts this collection squarely during Emperor Justinian’s reign, when Constantinople buzzed with ambition and plague in equal measure. Those 12 matching silver spoons weren’t just for soup – they were status symbols that screamed “old money” in an era when metal currency was becoming increasingly worthless. They’re basically the ancient equivalent of pulling up to the valet in a Bentley while the economy crashes around you.

2. Iron Crown Of Lombardy

Imagine needing serious legitimacy for your questionable claim to power. What do you do? If you’re a medieval ruler, you commission a crown allegedly containing metal from Jesus’s crucifixion. The Iron Crown of Lombardy represents history’s most successful branding exercise – a golden circlet containing what was marketed as a nail from the True Cross. Created around the 4th century, it transformed ordinary coronations into divine endorsements.

The crown’s genius lies in its unverifiable claim that makes skeptics look like heretics. From Charlemagne to Napoleon, power-hungry rulers lined up to place this accessory on their heads, essentially borrowing religious clout to silence political opponents. It’s the medieval equivalent of celebrities endorsing questionable products today – except instead of selling vitamins, it sold divine right to rule. The fact that museums still highlight this unproven relic connection shows how effective the original PR campaign remains fifteen centuries later.

1. Agate Casket Of Oviedo

While today’s billionaires donate buildings with their names plastered on the front, 10th-century Spanish King Fruela II wrote the original playbook on conspicuous giving. His donation to Oviedo Cathedral – a European pear wood box lined with gold arches and inlaid with exactly 99 precision-cut agates – wasn’t just generosity. It was political theater disguised as piety, designed to cement royal influence over the church.

The real kicker is the inscription threatening consequences for anyone removing it – the medieval equivalent of security tags that spray ink when removed from clothing. This casket represents the original church-state entanglement, where monarchs bought religious legitimacy through lavish gifts while religious institutions gained protection through royal association. The craftsmanship involved – perfectly fitting 99 stone pieces into gold settings – required skills more advanced than most contemporary jewelry production. It’s basically a thousand-year-old Supreme drop: limited edition, outrageously overproduced, and designed to flex wealth and access. If you enjoy going through history and exploring these ancient artefacts, then you might want to find out more about these mythical objects.